I remember talking to a taxi driver in Hakodate a while back. He told me about another foreigner who taught English in Japan. It didn't take long for that guy to get fed up with teaching, and he left the country with the lasting impression that Japanese people are just plain stupid.

Why? Well, Japanese students are moderately able to understand written English, but their conversation skills are extremely sub-par. I mentioned this before when talking about my speech contests students. They can memorize and recite paragraphs of difficult English, but they can't even answer when asked, "Did you study a lot?" It's an excruciating experience, being unable to communicate without writing everything down and giving them a few minutes to extrapolate a response.

As much as I empathize with the guy for his frustrating experiences, I don't agree with him. Yes, Japanese people seem to have a painstakingly difficult time picking up English. Sure, it gets frustrating. However, anyone qualified in the field of language teaching can easily tell why they're having such a hard time.

In a nutshell, it's the method they're using. It's hard to explain it in words, so I'll let this diagram do the explaining for me:

And herein lies the problem. Japanese teachers of English mistakenly believe that "native language" and "intended meaning" are the same thing. They believe that the only way to produce English is to start with Japanese, and then grind it through a grammatical translating machine. They think language is like math!

This becomes obvious when you see that English classes are taught almost exclusively in Japanese, no matter what the students' ability level. I looked at worksheets the teachers have created, and there are many activities that force students to translate each word in a sentence individually, and then do a big switch-a-roo in word order to abide by grammar rules. Imagine how hard it would be if you wanted to say something, like "I want to eat lunch."

From the overall meaning, the Japanese sentence would be 「昼食を食べたい。」

Then you'd break the words individually apart, and translate directly

into " lunch / eat / want to ". Then, you'd think of the grammar rules,

and reorder the sentence into " want to / eat / lunch ". Then you'd

remember the assumed subject, and finally end up with "I want to eat

lunch." All the time it took you to read that explanation is how much time a Japanese kid takes to construct and say this sentence. I literally have to stand and wait for MINUTES for a simple sentence. That's assuming they know all the translations and grammar rules. If they don't, this could take exponentially longer, but they usually just give up before then.

No, no, NOOOOOO! That's not how language works!! Native language is not the benchmark to base all other languages on! A language - any language, even your native language - is merely a path to express a desired meaning. Overall meaning is the genesis where all language should emerge from!

When I tried learning Japanese the first time, it felt a lot like what they do in Japan. I was terrible, and I could speak almost nothing. After a few years off, I decided to start over and learn Japanese again in a different location. This time, we spent very little time translating English to Japanese. For only the first week, we memorized simple everyday phrases. After that , we focused on learning the Japanese language from scratch using the basic building blocks of grammar and vocabulary. Of course, certain concepts still needed to be explained in English, but the first year was spent slowly constructing genuine Japanese and weeding English use out of the classroom. By the beginning of the second year, classes were already taught purely in Japanese. Not a single English word was spoken by the teacher, and yet we all had no problems understanding.

This is why we were successful. We constructed Japanese out of the meaning we wanted to express, bypassing English altogether. Of course, we had to give conscious effort to construct the sentences, but it was still pure Japanese. These days, when I speak Japanese, I'm also thinking in Japanese, so I can have a conversation at real-time speed.

This is why Japanese people can't speak English. It's not that the kids are stupid. They've just been doing it wrong. And, until someone with lots of power decides to make a radical change to the system, they will continue to do it wrong. My role here is to be an assistant to the teachers that insist on doing it wrong, so there is very little I can do to make an impact. It's like watching children play with toy guns, believing that they are preparing themselves for real combat.

Maybe that's what that guy meant when he called Japanese people "stupid." It's not the people learning who are stupid. It's the people who are teaching.

A story of discovery, food, fun, work, teaching, learning, culture, and society in the Japanese countryside.

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

Hilariously Lost in Translation

This post will be dedicated to some of the hilarious moments that occurred due to miscommunication/cultural differences:

1)

In elementary school, we were having a lesson on occupations. The teacher was telling kids what certain people do, and asked what the occupation was called in English. He got to the baker and asked, 「ぱんつくってる人は?」(pantsukutteru hito wa?). Some of the boys responded loudly with 「パンツを何??」 (they did WHAT with the panties?) because "pantsu kutteru hito" means 「パンツ食ってる人」, or "the person eating panties." The teacher repeated himself more slowly, saying 「パン、作ってる人」 (pan tsukutteru hito), which means "the person making bread." I laughed so hard I might have peed myself a little...

2)

In one of my elementary schools, I have the privilege of using this pointer:

Nobody seems to know what it represents. Around here, it's not uncommon to see people pointing at stuff with their middle finger, but its still leaves me a little unsettled. One time, I fixed the glove so that it was the index finger doing the pointing. The next time I went back to that school, someone had reverted it back to the original form. I guess they just like the symmetry of the middle finger or something.

3)

At yet another elementary school, a 5th grade student had this pencil box:

In this country, marijuana is strictly banned, to the point where possession of any small amount can get a foreigner jailed without trial for weeks or months, followed by deportation. Even so, the marijuana leaf symbol can be seen everywhere, strangely mostly on clothes and accessories meant for children. I've even seen ramen shop waitresses wearing bandanas with cannabis leaves printed all over it. It's just unusual to have the word "Marijuana" advertised so boldly on something, especially when accompanied by "I hear someone knocking on heaven's door." I laughed when I saw this pencil box, and the teacher explained to the child what it meant. I think the girl is considering getting a new pencil box hahaha.

4)

At one of my middle schools, some of the boys kept coming up to me and saying 「きらい だいいち」 (kirai dai'ichi). I was a little offended at first, because I thought they might be saying 「嫌い 第一」, which means "number one dislike," but they were using a different intonation pattern. 「嫌い 第一」 sounds like "kiRAi DAi'Ichi," but they were saying, "KIrai DAI'ichi."

After being confused for a few weeks, I found out that one of the second year boys, who everyone thinks is my doppelganger, is named 「きらい だいいち」 Kirai Dai'ichi, which I think is written as 喜来 大壱. This whole time, they were just calling me his name as a joke. I just never knew what was going on! I finally got it, and as I was chatting with their group, they all decided to nickname my clone "Kirai-en", or "Ki-Ryan". Fun times to come in the future...

5)

At my other middle school (you can see that I have many schools), the second-year kids were preparing a short speech about their "treasure" (See other blog post here for details). I was walking around helping the kids with vocabulary and grammar, when one of the girls raised her hand and called me over.

She wanted to know how to say the word "uncle". I said it out loud, /ʌŋkəl/. She repeated nicely after me, "uncle." I realized it might sound a little like another Japanese word, so I replied with, "Yes. Not ウンコ ("unko", which means "poop"), but 'uncle'." Everyone in class burst out laughing, while the girl turned beet-red and repeatedly spouted 「言ってない!言ってない!」 (I didn't say that!). I laughed with them, and assured her that she pronounced it well so she would calm down. Then I told her to read her sentence, which was, "I got [my treasure] from my uncle." She snorted, while the boys around her shouted "My unko! From my unko!" I laughed until I had a splitting side-ache, and the room was in an uproar.

The Japanese teacher of English (JTE) had stepped out of the classroom before all of this went down, and everything had mostly settled down before she came back. When the girl read her speech during the presentation, and she got to the "my uncle" part, the whole class tried their best to stifle their laughter. We all ended up snickering loudly, and the JTE looked around in confusion. I had to excuse myself to the corner to regain my composure while the girl covered her red face with her paper. After regaining some self control, we calmly returned to doing presentations, with the JTE none the wiser. Ahh I love my second-year students.

6)

Before going on stage in the school opening ceremonies (for the new school year), one of the other teachers came up to me and slowly said 「二年の先生について いってください」 (ninen no sensei ni tsuite itte kudasai). This can mean 「二年の先生について言って下さい」, which means "please say [something] regarding the second year teachers." I was specifically told that I didn't need to prepare a speech, so I freaked out and asked her, "What would you like me to say?" She gave me a confused look, and then repeated what she said before, but a little faster. At natural speed, I picked up the intonation difference and realized that she said 「二年の先生に付いて行って下さい」,which means "please follow the second year teachers [up the stage]." I breathed a sigh of relief, and angrily muttered to myself, "you coulda just said it like that the first time..."

Thanks for reading! If any other funny stuff happens, I may make a new post, or just add more to this post. Stay tuned!

1)

In elementary school, we were having a lesson on occupations. The teacher was telling kids what certain people do, and asked what the occupation was called in English. He got to the baker and asked, 「ぱんつくってる人は?」(pantsukutteru hito wa?). Some of the boys responded loudly with 「パンツを何??」 (they did WHAT with the panties?) because "pantsu kutteru hito" means 「パンツ食ってる人」, or "the person eating panties." The teacher repeated himself more slowly, saying 「パン、作ってる人」 (pan tsukutteru hito), which means "the person making bread." I laughed so hard I might have peed myself a little...

2)

In one of my elementary schools, I have the privilege of using this pointer:

|

| Flippin' the bird at little kids |

3)

At yet another elementary school, a 5th grade student had this pencil box:

|

| Reefer for the little-uns |

4)

At one of my middle schools, some of the boys kept coming up to me and saying 「きらい だいいち」 (kirai dai'ichi). I was a little offended at first, because I thought they might be saying 「嫌い 第一」, which means "number one dislike," but they were using a different intonation pattern. 「嫌い 第一」 sounds like "kiRAi DAi'Ichi," but they were saying, "KIrai DAI'ichi."

After being confused for a few weeks, I found out that one of the second year boys, who everyone thinks is my doppelganger, is named 「きらい だいいち」 Kirai Dai'ichi, which I think is written as 喜来 大壱. This whole time, they were just calling me his name as a joke. I just never knew what was going on! I finally got it, and as I was chatting with their group, they all decided to nickname my clone "Kirai-en", or "Ki-Ryan". Fun times to come in the future...

5)

At my other middle school (you can see that I have many schools), the second-year kids were preparing a short speech about their "treasure" (See other blog post here for details). I was walking around helping the kids with vocabulary and grammar, when one of the girls raised her hand and called me over.

She wanted to know how to say the word "uncle". I said it out loud, /ʌŋkəl/. She repeated nicely after me, "uncle." I realized it might sound a little like another Japanese word, so I replied with, "Yes. Not ウンコ ("unko", which means "poop"), but 'uncle'." Everyone in class burst out laughing, while the girl turned beet-red and repeatedly spouted 「言ってない!言ってない!」 (I didn't say that!). I laughed with them, and assured her that she pronounced it well so she would calm down. Then I told her to read her sentence, which was, "I got [my treasure] from my uncle." She snorted, while the boys around her shouted "My unko! From my unko!" I laughed until I had a splitting side-ache, and the room was in an uproar.

The Japanese teacher of English (JTE) had stepped out of the classroom before all of this went down, and everything had mostly settled down before she came back. When the girl read her speech during the presentation, and she got to the "my uncle" part, the whole class tried their best to stifle their laughter. We all ended up snickering loudly, and the JTE looked around in confusion. I had to excuse myself to the corner to regain my composure while the girl covered her red face with her paper. After regaining some self control, we calmly returned to doing presentations, with the JTE none the wiser. Ahh I love my second-year students.

6)

Before going on stage in the school opening ceremonies (for the new school year), one of the other teachers came up to me and slowly said 「二年の先生について いってください」 (ninen no sensei ni tsuite itte kudasai). This can mean 「二年の先生について言って下さい」, which means "please say [something] regarding the second year teachers." I was specifically told that I didn't need to prepare a speech, so I freaked out and asked her, "What would you like me to say?" She gave me a confused look, and then repeated what she said before, but a little faster. At natural speed, I picked up the intonation difference and realized that she said 「二年の先生に付いて行って下さい」,which means "please follow the second year teachers [up the stage]." I breathed a sigh of relief, and angrily muttered to myself, "you coulda just said it like that the first time..."

Thanks for reading! If any other funny stuff happens, I may make a new post, or just add more to this post. Stay tuned!

Sunday, April 7, 2013

Trip to Nagano

Since I came to Japan, I've been down to visit my girlfriend in Nagano twice. She lives in a sleepy town called Komagane, boasting a population of 30,000 people and nestled in a valley in the Japanese Central Alps.

I usually avoid going down to visit her. The town itself is very hard to get to because it's so tucked away, so the nearest bullet train station and airport are hours away. I always take the highway bus, which is cheap (about ¥2000 one way) but takes about 4 hours from Tokyo (not including the additional 10 hours overnight from Aomori to Tokyo). She also lives in a very small apartment about the size of a single-person college dorm room, with added tiny bathroom and kitchenette. In town, there is very little to do, especially when you don't have a car because the bus system is insufficient. Essentially, it's a pretty big waste of time and money to go down to Komagane compared to having her take a trip up to Aomori to visit me.

Nevertheless, it's necessary to give her a break from traveling once in a while and return the favor. This past long weekend, I made the trek down to Komagane. The first time I visited, we hardly did anything because she didn't really have a good idea of the area. This time, we had done more planning and rented a car, so there was more to occupy ourselves with.

First, we went to 光前寺 (Kozenji Temple). I've been a little tired of visiting shrines and temples lately (there are just SO many), but this one was pretty special. Everything was built out of untreated wood, so the structures looked very natural and blended well with the tall cedar trees surrounding the area. They were all very intricately carved too, and I admired the craftsmanship. However, untreated wood is also defenseless against pests, so bugs burrowed millions of tiny holes into the pretty pagoda.

Next, we shifted over to a nearby riverside park to relax. As we walked through the long but somewhat barren park, we got to a playground area. There was a climbing wall (which was unfortunately cordoned off) as well as some really nice playground equipment, like a long roller slide and a rope climbing tower. Always one who likes to frolic, I raced my girlfriend up and down the rope tower (she lost both times and called me a monkey), and then we took a ride down the slide. Roller slides are fast and fun, and give you a good massage on the way down too!

We got hungry, so we decided to try a Brazilian food restaurant the other JETs recommended. We had a hard time finding the place, and when we finally walked in, we were greeted by the most apathetic people I've ever met. No greeting. No showing us to our seats. No handing us menus. All we got was a stare from a gangster-looking tattooed Brazilian guy at the bar and a glance from the woman in the kitchen. It almost felt like we accidentally waltzed into their living room and they wanted us out. Anyways, we sat down where we wanted and scrounged up some menus from another table. As we were about to order, it dawned on us that we had no idea what language to order in. The menu was entirely in Portuguese, and not a single Japanese word was written anywhere in the shop. Kristin just did her best using Spanish pronunciations to order some sandwiches (that was all they really had), and sat back down. While we were eating, nobody else came in except for another gangster-looking Brazilian dude, who biked up on his expensive downhill bike and fist-bumped the other guy before joining him at the bar. We just finished as quickly as we could and left. Outside, we were baffled by what just happened, and how the hell a shop like that could survive, let alone even exist, in this place. Awkward.......

With out bellies full, we drove through a tunnel to get to another valley called Kiso Valley, home of the Kiso Post Towns. These towns are historical trade points of the Kisoji, an old trade and travel route connecting the old and new capitols, Kyoto and Tokyo. The town we went to was called Narai, which was the richest of the Kiso Post Towns back in the day. It turned out to be more boring and less authentic than I was hoping. The preservation area itself was only a single strip running through an obviously more modern town. Many of the "preserved buildings" were merely more modern buildings disguised as traditional ones. The road is paved with cement, and cars swerve through occasionally. The box style lamps hanging from the buildings seem traditional, until you realize they run on energy-saving compact fluorescent bulbs. The place was pretty deserted, as it was a cold and windy day. Many of the places were closed, and the places that were open tended to be shops selling stereotypical Japanese trinkets for exorbitant prices. I will not pay $30 for a little wooden comb, thank you very much. The whole place just reeked of "tourist trap." It was such a let down that I didn't even feel obligated to take a picture of the place, so you'll have to settle for a stock photo.

Taking a break from all the disappointment, we stopped in a small shop to eat some of the local specialty: お焼 oyaki. Oyaki is a fried, steamed, and flipped bun stuffed with different kinds of goodies. We ordered ones filled with pumpkin, 野沢菜 "nozawana" pickled greens, and しめじ "shimeji" mushrooms. They were quite good and surprisingly inexpensive, and helped to lift my mood. We took a 肉まん mean bun home with us before we left the town for good.

That night, we decided to get some pizza. I haven't had pizza since I came to Japan, so hooray! We went up to a place called Oz Pizza, which turned out to be a B&B cabin in the woods in the foothills. We ordered a pepperoni pizza, which was fresh from the wood-fired stove. It was ridiculously expensive ($35 for something equivalent to a small pizza), but it was nice to actually have some real mozzarella cheese instead of the sweet candy-like dairy product Japanese people like to call cheese.

That pretty much ended the bizarre weekend. The next day, before I got back on the bus and headed back home, we ate lunch at a local gyoza shop that Kristin had always wanted to try. It was run by a nice old lady with golden teeth, and their prices were fantastic. We both got set menus, and shared the mapo tofu and gyoza that came with them. The gyoza were tasty and stuffed to the brim, unlike the loose saggy ones with very little filling at other places. Kristin kicked herself a few times for not trying the place sooner, and we left to the bus terminal.

Goodbye Komagane, and here's hoping that we never encounter each other again!

I usually avoid going down to visit her. The town itself is very hard to get to because it's so tucked away, so the nearest bullet train station and airport are hours away. I always take the highway bus, which is cheap (about ¥2000 one way) but takes about 4 hours from Tokyo (not including the additional 10 hours overnight from Aomori to Tokyo). She also lives in a very small apartment about the size of a single-person college dorm room, with added tiny bathroom and kitchenette. In town, there is very little to do, especially when you don't have a car because the bus system is insufficient. Essentially, it's a pretty big waste of time and money to go down to Komagane compared to having her take a trip up to Aomori to visit me.

Nevertheless, it's necessary to give her a break from traveling once in a while and return the favor. This past long weekend, I made the trek down to Komagane. The first time I visited, we hardly did anything because she didn't really have a good idea of the area. This time, we had done more planning and rented a car, so there was more to occupy ourselves with.

First, we went to 光前寺 (Kozenji Temple). I've been a little tired of visiting shrines and temples lately (there are just SO many), but this one was pretty special. Everything was built out of untreated wood, so the structures looked very natural and blended well with the tall cedar trees surrounding the area. They were all very intricately carved too, and I admired the craftsmanship. However, untreated wood is also defenseless against pests, so bugs burrowed millions of tiny holes into the pretty pagoda.

|

| Amazing untreated wood. |

|

| The pests thought so too. They didn't allow people to stand on it because it was so structurally compromised. |

We got hungry, so we decided to try a Brazilian food restaurant the other JETs recommended. We had a hard time finding the place, and when we finally walked in, we were greeted by the most apathetic people I've ever met. No greeting. No showing us to our seats. No handing us menus. All we got was a stare from a gangster-looking tattooed Brazilian guy at the bar and a glance from the woman in the kitchen. It almost felt like we accidentally waltzed into their living room and they wanted us out. Anyways, we sat down where we wanted and scrounged up some menus from another table. As we were about to order, it dawned on us that we had no idea what language to order in. The menu was entirely in Portuguese, and not a single Japanese word was written anywhere in the shop. Kristin just did her best using Spanish pronunciations to order some sandwiches (that was all they really had), and sat back down. While we were eating, nobody else came in except for another gangster-looking Brazilian dude, who biked up on his expensive downhill bike and fist-bumped the other guy before joining him at the bar. We just finished as quickly as we could and left. Outside, we were baffled by what just happened, and how the hell a shop like that could survive, let alone even exist, in this place. Awkward.......

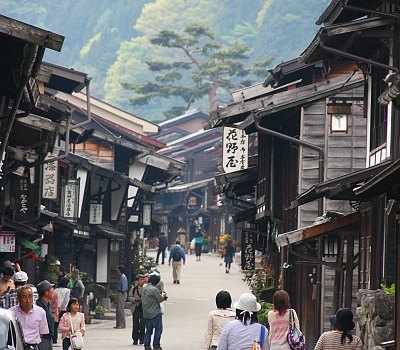

With out bellies full, we drove through a tunnel to get to another valley called Kiso Valley, home of the Kiso Post Towns. These towns are historical trade points of the Kisoji, an old trade and travel route connecting the old and new capitols, Kyoto and Tokyo. The town we went to was called Narai, which was the richest of the Kiso Post Towns back in the day. It turned out to be more boring and less authentic than I was hoping. The preservation area itself was only a single strip running through an obviously more modern town. Many of the "preserved buildings" were merely more modern buildings disguised as traditional ones. The road is paved with cement, and cars swerve through occasionally. The box style lamps hanging from the buildings seem traditional, until you realize they run on energy-saving compact fluorescent bulbs. The place was pretty deserted, as it was a cold and windy day. Many of the places were closed, and the places that were open tended to be shops selling stereotypical Japanese trinkets for exorbitant prices. I will not pay $30 for a little wooden comb, thank you very much. The whole place just reeked of "tourist trap." It was such a let down that I didn't even feel obligated to take a picture of the place, so you'll have to settle for a stock photo.

|

| Narai-juku on a warmer and busier day. |

|

| Different kinds of oyaki. We had the three on the left. |

That pretty much ended the bizarre weekend. The next day, before I got back on the bus and headed back home, we ate lunch at a local gyoza shop that Kristin had always wanted to try. It was run by a nice old lady with golden teeth, and their prices were fantastic. We both got set menus, and shared the mapo tofu and gyoza that came with them. The gyoza were tasty and stuffed to the brim, unlike the loose saggy ones with very little filling at other places. Kristin kicked herself a few times for not trying the place sooner, and we left to the bus terminal.

Goodbye Komagane, and here's hoping that we never encounter each other again!

Solo Day

This past weekend, when the weather was beautiful and possibly even considered not cold, I decided to take a day and go explore the west side of the city by myself, with nothing other than my bike. The title is a bit strange, since I tend to do a lot of stuff by myself around here, but it was nice to go out and do things at my own pace. I wanted to see how far I could get before I pooped out, since I'm hoping to ride a roughly 40-50 km trip up to Mt. Hakkoda and back during the spring.

For now, the original plan was to ride along the curving coastal highway going northwest, and see how far out of the city I could get. The day before I left, I was looking through a picture book of the region, and I happened across a picture of 野木和公園 Nogiwa Park, with beautiful bridges going across a picturesque lake. I decided I'd take a western detour to bike around the park before continuing north. I also looked up a ramen shop called ラーメン二八〇 「ニッパーマル」 (since the highway is called the 280) far down along the highway, which I could use as a rest stop/landmark.

And so, around 11:30 am after a breakfast of rice, natto, and a quarter of a honeydew, I set out. The roads in the city are bumpy and crowded, and no fun to ride. I ground through it over the bay bridge, and finally made a left in 油川 Aburakawa to get to Nogiwa Park. None of the paths going through the park are paved, so I stayed along the road that winds around it. The lake itself had not yet completely unfrozen, and still had large chunks of ice covering most of the water surface. I wonder if there are any ice skating activities here during the deep winter, although perhaps the deep snow and not-quite-low-enough temperatures make it impossible. Even though the ice wasn't all melted yet, the lake shore was teeming with fisherman, so I guess this is a local fishing mecca.

I took half a loop around the east side of the park (which ended in a dirt road), and then wound back around to the west side. I saw a road sign and asked myself, "Do I want to go to 五所川原 Goshogawara?" which is maybe 40 km to the southwest. I thought about it, and decided, "Nahh..." but then I saw the road...

Luscious curves and gentle hills, occasionally enveloped in green pine forests and lined with unadulterated white snow like icing on a cake? How can anyone resist that? So, I rode up this winding, silky smooth, and absolutely empty road for a few miles until I hit a roadblock that said, "Closed for the winter." So that's why it was so empty...

Having been forced to turn around, I rejoined the coastal highway and continued north. A south-blowing wind of around 5 m/s made the riding slow and excruciating. I kept plowing on hoping for the ramen shop sign to appear around the next bend. After a grueling who-knows-how-long, I finally made it to Ramen 280 next to 北中). After re-teaching myself how to walk on solid ground, I stepped inside.

The place was mostly empty, except for the chef and one guy in the corner taking his sweet time reading a magazine. This was great, because I could stretch my poor legs without people judging me. I ordered the shop's specialty, 味噌担々麺 (miso tantan-men) and sprawled out on the tatami in the unoccupied corner to stretch and watch some daytime Japanese television. When my food came, it didn't disappoint.

It had a sweet and savory flavor made through the use of lots of sesame sauce. It was also filled with chashuu pork and an indescribable ground meat that formed a pebble soup-bed underneath it all. I thought it wasn't that spicy at first, but then the mouth burning slowed my pace way down.

I checked out the wall behind me, and apparently this shop has a spicy ramen challenge. On the left, it says 眺望山「噴火」ラーメン Choubouzan Funka (eruption) Ramen for 800 yen. It advertises that the ramen is very spicy, but if you finish it, soup and all, in under 28 minutes, you get it for 280 yen. I think I'll pass and just come back on the 28th of every month, when the 正油 shouyu ramen is 280 yen. Notice a theme?

Anyways, after chilling out here for about an hour, I finally felt ready to go again. I started heading north even further, but the wind demoralized me so much that I turned back around after a kilometer or so. The ride back home was fast and easy with the wind behind me.

After getting home, my legs were surprisingly fine. I'd clocked in a bit more than 40 km, and yet 2 days later I still don't feel anything especially sore. I'll probably still need to do some more training before taking on Hakkoda, and I'll try to go further down that fine road towards Goshogawara once it opens up again. In any case, I felt a bit accomplished, even though I spent the entire day by myself. I'm used to it by now, I suppose, but it'll be great once my girlfriend can finally come up and live with me again.

For now, the original plan was to ride along the curving coastal highway going northwest, and see how far out of the city I could get. The day before I left, I was looking through a picture book of the region, and I happened across a picture of 野木和公園 Nogiwa Park, with beautiful bridges going across a picturesque lake. I decided I'd take a western detour to bike around the park before continuing north. I also looked up a ramen shop called ラーメン二八〇 「ニッパーマル」 (since the highway is called the 280) far down along the highway, which I could use as a rest stop/landmark.

And so, around 11:30 am after a breakfast of rice, natto, and a quarter of a honeydew, I set out. The roads in the city are bumpy and crowded, and no fun to ride. I ground through it over the bay bridge, and finally made a left in 油川 Aburakawa to get to Nogiwa Park. None of the paths going through the park are paved, so I stayed along the road that winds around it. The lake itself had not yet completely unfrozen, and still had large chunks of ice covering most of the water surface. I wonder if there are any ice skating activities here during the deep winter, although perhaps the deep snow and not-quite-low-enough temperatures make it impossible. Even though the ice wasn't all melted yet, the lake shore was teeming with fisherman, so I guess this is a local fishing mecca.

|

| Nogiwa Lake, filled with slushy water. |

I took half a loop around the east side of the park (which ended in a dirt road), and then wound back around to the west side. I saw a road sign and asked myself, "Do I want to go to 五所川原 Goshogawara?" which is maybe 40 km to the southwest. I thought about it, and decided, "Nahh..." but then I saw the road...

|

| Sweet mother of road biking... |

Luscious curves and gentle hills, occasionally enveloped in green pine forests and lined with unadulterated white snow like icing on a cake? How can anyone resist that? So, I rode up this winding, silky smooth, and absolutely empty road for a few miles until I hit a roadblock that said, "Closed for the winter." So that's why it was so empty...

Having been forced to turn around, I rejoined the coastal highway and continued north. A south-blowing wind of around 5 m/s made the riding slow and excruciating. I kept plowing on hoping for the ramen shop sign to appear around the next bend. After a grueling who-knows-how-long, I finally made it to Ramen 280 next to 北中). After re-teaching myself how to walk on solid ground, I stepped inside.

The place was mostly empty, except for the chef and one guy in the corner taking his sweet time reading a magazine. This was great, because I could stretch my poor legs without people judging me. I ordered the shop's specialty, 味噌担々麺 (miso tantan-men) and sprawled out on the tatami in the unoccupied corner to stretch and watch some daytime Japanese television. When my food came, it didn't disappoint.

|

| Miso Tantan-men |

I checked out the wall behind me, and apparently this shop has a spicy ramen challenge. On the left, it says 眺望山「噴火」ラーメン Choubouzan Funka (eruption) Ramen for 800 yen. It advertises that the ramen is very spicy, but if you finish it, soup and all, in under 28 minutes, you get it for 280 yen. I think I'll pass and just come back on the 28th of every month, when the 正油 shouyu ramen is 280 yen. Notice a theme?

|

| やんべ、やんべ、チョウやんべ! |

After getting home, my legs were surprisingly fine. I'd clocked in a bit more than 40 km, and yet 2 days later I still don't feel anything especially sore. I'll probably still need to do some more training before taking on Hakkoda, and I'll try to go further down that fine road towards Goshogawara once it opens up again. In any case, I felt a bit accomplished, even though I spent the entire day by myself. I'm used to it by now, I suppose, but it'll be great once my girlfriend can finally come up and live with me again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)